When Reshan Richards and I are working with leaders on a very pragmatic level, we often find ourselves thinking about meetings. That’s where leaders spend a lot of their time, advance a lot of their projects, and solve a lot of their problems.

Some meetings are set in advance and repeat. These are sometimes called “standing meetings.”

Other meetings are called to address a specific need / solve a problem / deal with an urgency. These are often referred to as “impromptu” or “just-in-time” meetings.

If you’re calling and leading one of the latter, the meeting can be greatly enhanced by adding some simple calendar discipline to your routine.

Here’s what we suggest:

First, find a time for the meeting in a way that doesn’t clutter up people’s inboxes. So, instead of emailing the group and asking each member to share his or her availability, precipitating a blizzard of REPLY ALLs, send a Doodle Poll or build a quick table in Google Docs to allow people to give their input once. Then, you can make a decision about the best possible date and time and invite the participants.

You can invite people in one of two ways. You can send them an email with the pertinent details, or you can skip that step — recommended — and send them a calendar invite that appears on their calendar and allows them to accept it.

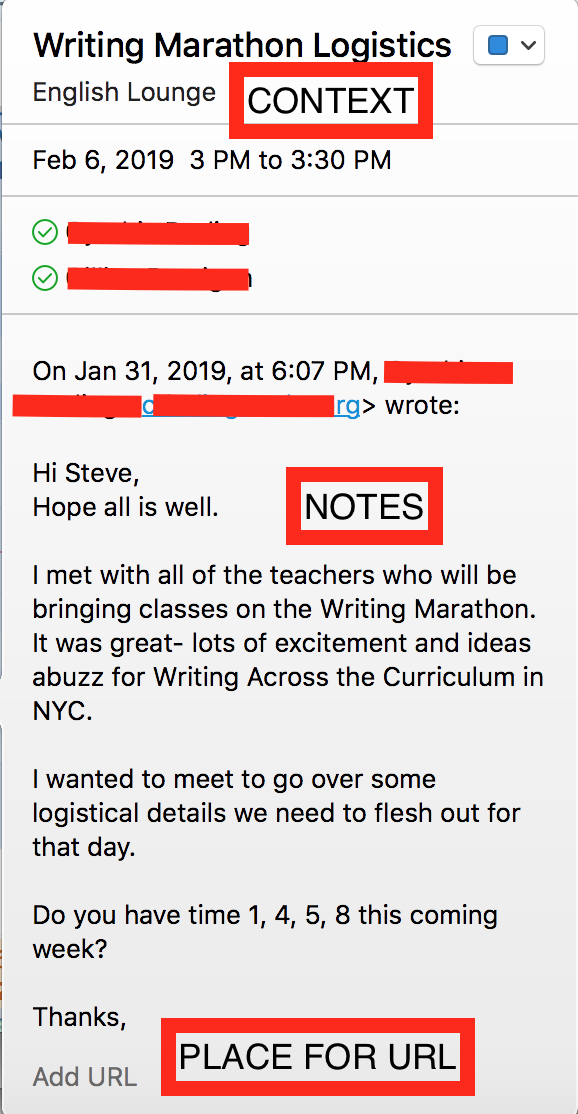

Let’s drill down into the calendar invite process, because that’s where many leaders can still improve. Start with a good, general title that tells people the purpose of the meeting. Then, add as much contextual information as you can, including the time and the location of the meeting. Finally, and one layer deeper, add any relevant notes.

Purpose, context, and notes embedded in the calendar invite itself: these items allow the event marker to function as a form of “glance media” for the meeting participants. They can read it when they are preparing for the meeting, or if they are too rushed to prepare, the event marker can, at the very least, help them to attain a just-in-time understanding of the meeting on their way into the meeting.

Once the meeting is shared in that manner, you can feel that you’ve taken some important steps to help meeting participants take responsibility for their part of the meeting. You might share an agenda at some point or share one at the meeting.

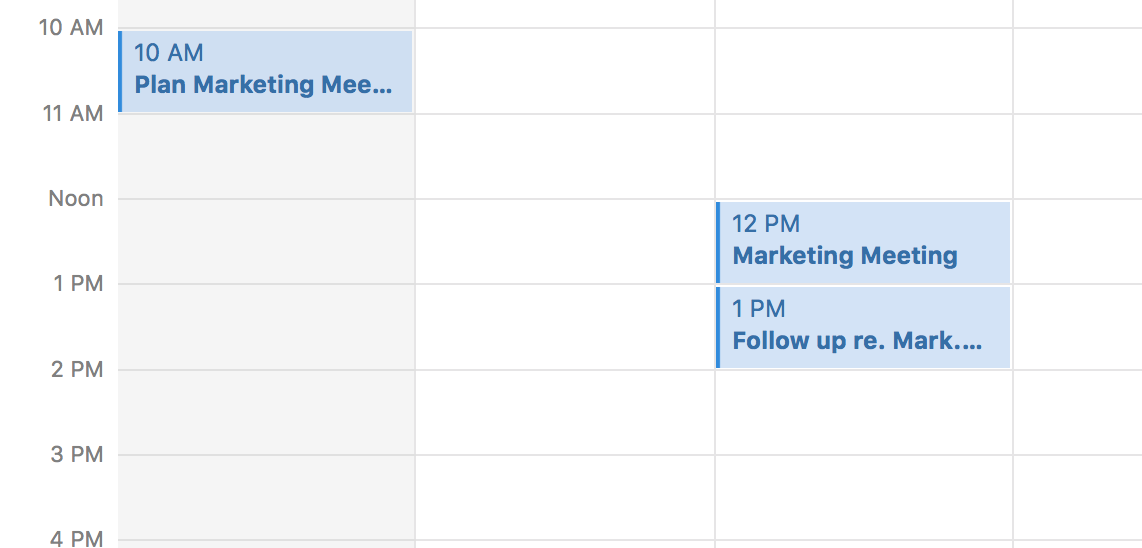

At any rate, your next set of steps involve your own calendar, and your own level of responsibility for a meeting that you called. Go to your own calendar and schedule the BEFORE and the AFTER work that will make the meeting a success. We like to schedule our planning sessions two or more days out and our follow-up sessions immediately after the meeting. You’ll notice in the example below that the planning session and the follow-up session are as long as the actual meeting. That’s an ideal time distribution. Both can be condensed as needed, or to create found time in your schedule if you do what you need to do in 25 minutes.

This three part discipline — creating detail rich event markers and then scheduling your Pre and Post- meeting work — allows you to take seriously what it takes to plan, execute, and carry forward an effective meeting.