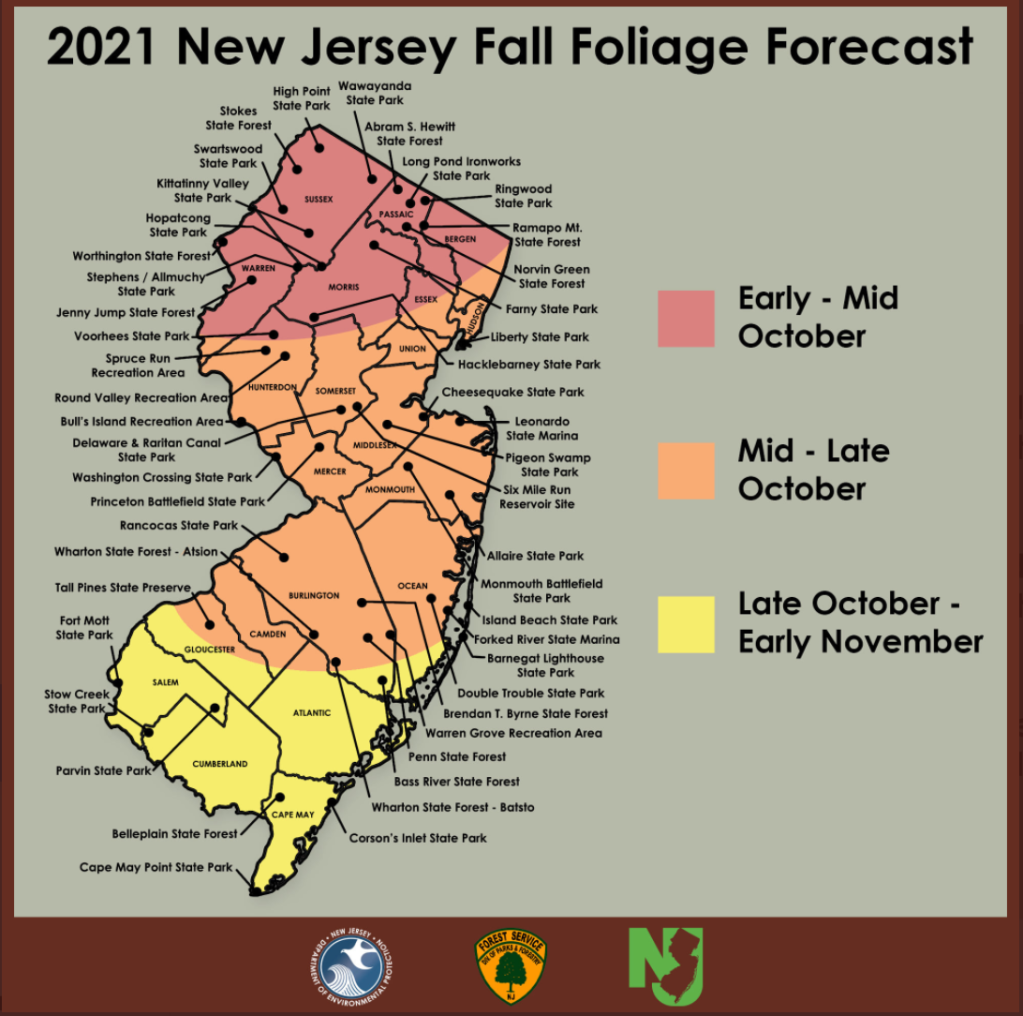

I had a conversation with a friend, colleague, and coach a few days ago, and it caused me to dig up a speech I gave a decade ago to a group of Sussex County (New Jersey) high school students. I’m posting it today because (a) I couldn’t find it in the RW archives, (b) it holds up as an homage to a few things I still care about, and (c) it captures some wisdom from the best coach I ever had. Interestingly, I’ve been thinking about him a lot lately because he recently moved out of New Jersey and a few tributes came through my email from his friends and neighbors. The world seems best when it’s enlivened by warm connections. Blogs, too.

I want to begin by congratulating all the Scholar Athletes here tonight. It’s rare to be recognized for excellence in one category . . . and even more rare to be recognized for both your athleticism and your accomplishments in the classroom.

And so it is first and foremost humbling to address you and even more to try to fulfill my charge, which is to leave you with something of value. But I will try.

I graduated from Pope John High School in 1994, and I was fortunate enough to be a Scholar Athlete, too. I think the standards must have been lower back then. My father tells me that when I attended this same dinner, I actually fell asleep during the speaker’s remarks . . . so I’ll understand if some of you nod off. What comes around goes around.

I make my living in a few ways. I’m an administrator at the Montclair Kimberley Academy in Montclair, New Jersey, and I write books and magazine articles. These activities, especially the latter, have allowed me to travel and meet interesting people and build a small audience of “fans” who follow the work that I do.

But none of these things qualify me to speak to you today.

What qualifies me, I think, is a respect and reverence for the time of life that you are on the verge of completing. I’m a firm believer that high school is not just a pathway to college. It’s not a means to an end. It’s a process that can give you much of what you need to build a successful life.

Sure, you will need to pick up certain skills to be a surgeon or a lawyer, but high school can give you the intangibles – it can teach you about how to treat people and how not to treat people; it can teach you about how to pursue your dreams with honesty and integrity. It can help you establish, in other words, firm foundations for your character and your ethics.

I’m not implying that you have to go out and learn these things tomorrow. The fact is, you have already had the experiences. Maybe in your freshmen year. Maybe last week. You just have to go back to them, dust them off, pull out the lessons, and return to them as needed.

For me, two moments in high school stand out as particularly instructive. They guide me almost daily, since they relate to teamwork, on the one hand, and individual performance, on the other.

Since basketball was pretty much my life in high school, these are both basketball stories. I’m going to tell them to you today not only to share the lessons, but also to model for you the process of learning from your past and particularly of learning from your high school experiences.

The first story is called “The Worst Best Team in Sussex County.”

When I was a sophomore, I was lucky enough to be called up the Varsity team – or so I thought. The team was filled with great seniors. They could shoot the lights out and play great defense. They were physically tough and aggressive. A few of them were even college prospects. I was excited to lace up my shoes next to them. But the shine only lasted a few days, a few practices. I quickly realized there was something wrong with the team. I was young, so I couldn’t put my finger on it. But something just didn’t feel right in the locker room or on the bus. Something just didn’t feel right on the court. We were losing games we shouldn’t have lost, and barely winning games we should have won by double digits.

I’ll never forget the practice when my coach told us to meet in the film room rather than on the court. We crowded around the television as my coach played a video he had edited together from various games. There were two scenes in the video. In the first one, one of our players fell down. He had taken a pretty hard hit; the ref blew the whistle; the game stopped. Eventually, he pulled himself off the floor and walked to the foul line.

The second scene was more exciting and more of what we expected to see in a highlight film – one of our players dribbled the ball past a few defenders and dunked it.

Our coach let us watch each scene a few times, and then he asked us what we noticed. We described the dunk but said that the rest was pretty boring. He played both scenes again – and eventually we were silent. We didn’t notice what he wanted us to notice. An orchestrated tension mounted. And then coach cut in:

In the first scene, when one of our players fell, no one helped him back to his feet. Not a single teammate offered him a hand. In the second scene, when one of our players dunked the ball, a crowing achievement for a high school basketball player from Sussex County, no one on our team gave him a high five or a pat on the back. No one celebrated with him or because of him. He looked around, expectantly, and then ran back down the court.

“These two scenes tell the whole story of our season,” coach said. “They demonstrate exactly why we aren’t winning more games and exactly why we haven’t yet lived up to our potential.”

He was right. And he’s still right.

You can be the greatest athlete on the court or the smartest person in your company . . . but if you can’t make your team work with you, if you can’t build a great team around you, you will never go as far as you should. You can’t win a team game alone, and most of what you will do in your lives, outside the classroom, is a team game. When you’re asked to collaborate on a group project in college . . . when you’re part of a study group in law school . . . when you organize an event for charity . . . when you start a family. . . All of these are team games. And if you don’t help your teammates off the ground when they stumble or pat them on the back when they soar, your teams will underachieve. You will underachieve.

The second story is called “The Worst Best Pass of My Life.” This one involves the same coach in a different season. It was my senior season this time, and my team was having a good year – a much better year, in fact, than we should have been having. With only a few seniors on the team, and only one senior with any true experience, we were exceeding all expectations, winning games we shouldn’t have been winning, and blowing out teams we should have only beat by a few points. I was certainly a little bit arrogant by the mid-point of the season.

In one game, a game we were easily winning, I caught a long rebound near the left side of the court. I looked down the court and saw one of my teammates streaking toward the basket. I reached back like a quarterback and launched a “hail mary” style pass – he caught it and laid it in while getting fouled. The crowd went wild — so wild, in fact, that I didn’t hear my teammate calling my name when he came in to replace me. My coach had pulled me out of the game right after the pass, and he left me at the end of the bench for the rest of the game.

I was outraged and humiliated, and I sulked until I had the chance to confront him the next day.

“Why’d you bench me, coach?” I asked him.

His answer was precise: “When you throw a pass like that, everyone in the gym can tell exactly where the ball is going. That pass only worked because the team we were playing wasn’t very good. If you throw that pass against a great team, they’re going to steal it. And if you throw that pass at the wrong time in the game against a great team, we’re going to lose. It’s my job to make sure that doesn’t happen. It’s your job, as my team captain, to understand.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise to you that my coach, Tom Fox, won hundreds of games and ended his career as a local legend. At that moment, he was teaching me about the way the smallest details contribute to our success and our failure. To have enduring greatness, to win seasons instead of just games, to have a great career, you have to practice perfectly. You have to practice the way you hope to play – whether you’re playing the game of basketball or the game of life.

You’ll notice a trend in each of these stories. They are all about failures. A failing team, a moment when a coach benched a player: if you had asked me when I was your age if I would talk about these moments in public when I was my age, I would have laughed in your face. Not a chance.

It’s difficult to try to learn from failure while it’s happening . . . it’s much easier to try to learn from a day like today, where someone else is telling you that you’ve made it – where the stars seem to be aligned and the applause is tied directly to your actions and efforts. Don’t get me wrong, I hope you enjoy the rest of the evening . . . you deserve it. Being named your school’s “Scholar Athlete” is pretty great. I hope you enjoy the rest of the things that go well in your high school careers and beyond. But don’t forget about the things that don’t go well or that didn’t go well. Don’t bury these experiences. They just might contain lessons that will last, lessons you can return to as you shape a meaningful, productive, and happy life. Lessons you might share one day in a speech wherein you’re actually trying to pass on something of value.