Reshan and I have been adding resources to the “Toolkit” section of the Make Yourself Clear website. Take a look.

Reshan and I have been adding resources to the “Toolkit” section of the Make Yourself Clear website. Take a look.

In a recent profile of Robert Caro, David Marchese asks Caro about his practice of planning his books.

I know that when you’re planning your books, you write a couple paragraphs for yourself that explain what the books are about, and then you use those paragraphs as a North Star to guide your writing and outlining.

This, and one additional question, leads Caro to demonstrate how the technique works in practice. How it helps him to tell the right stories and eliminate stories that, though they are interesting or compelling, don’t connect to his “North Star” paragraphs. How it serves as a kind of invisible fence around the province of his subject. Caro explains, vis-à-vis his magisterial Master of the Senate:

Here’s how I boiled that book down: I said that two things come together. It’s the South that raises Johnson to power in the Senate, and it’s the South that says, “You’re never going to pass a civil rights bill.” So to tell that story you have to show the power of the South and the horribleness of the South, and also how Johnson defeated the South. I said, “I can do all that through Richard Russell,” because he’s the Senate leader of the South, and he embodies this absolute, disgusting hatred of black people. I thought that if I could do Russell right, I wouldn’t have to stop the momentum of the book to give a whole lecture on the South and civil rights. What I’m trying to say is that if you can figure out what your book is about and boil it down into a couple of paragraphs, then all of a sudden a mass of other stuff is much simpler to fit into your longer outline.

nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/01/magazine/robert-caro-working-memoir.html

Clarity is always about choices, or, as the old writer’s dictum goes, “having the guts to cut.” It helps one’s confidence in such cutting to boil things down, to trim along the edges of the shadow cast from a clear North Star.

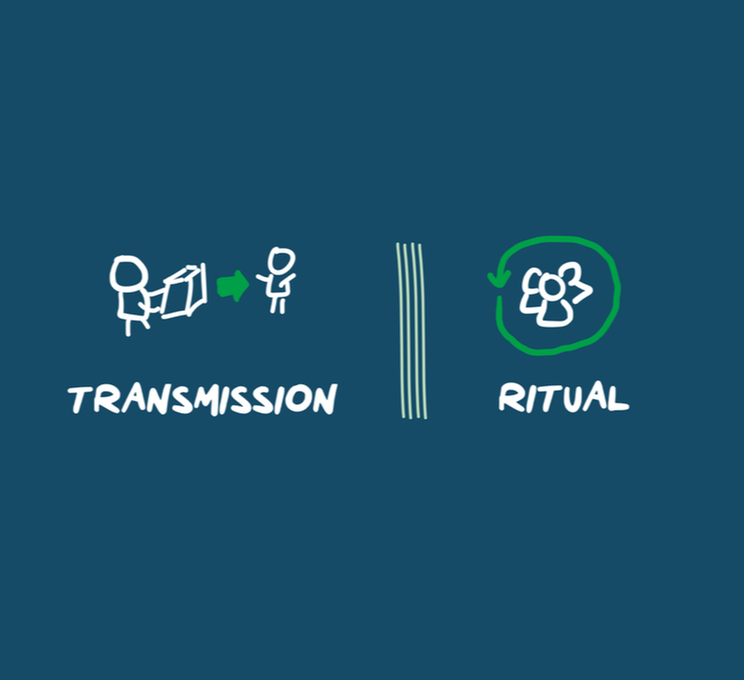

If you read this blog everyday, the following image (built by Reshan Richards) will push you to think back on an earlier post. As a teacher, in my classroom, I’m constantly concerned with finding tie-ins to former lessons, books, conversation . . . and this activity helps students to activate prior knowledge or build new knowledge.

Sometimes I forget that this blog is like a classroom, too. I should be using some of the same moves that I use in my classroom. But I didn’t forget today. If you’ve been reading faithfully, see if you can recall the post to which the image refers. And if you’re new to the blog today, or haven’t read it in a while, go digging in the recent archives. See what kinds of connections you can make.

This past week I wrote posts about:

Now they’re all in one place for you, easily accessible as you sip your morning coffee and make your weekend plans.

I started re-reading Peter Drucker’s The Effective Executive, and one of the first points he makes is that effectiveness begins with an understanding of where your time goes. I’ve read this and agreed with it many times, but for some reason, I’ve never actually implemented it. I’ve never actually kept track of where my time goes.

If I don’t do that, then I can’t assess if I’m actually using my time effectively. I can’t assess if I’m prioritizing appropriately. And, ultimately, I can’t adjust or improve. So, here goes. Here’s where my time went this week, between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m., Monday through Friday.*

*I tend to work outside of these hours, as well, but I think it’s best, for the purposes of this experiment, to focus on what happens within the proverbial 40-hour workweek. As I become better at tracking my time, perhaps I will extend into mornings and evenings.

Today, while discussing Julius Caesar with my ninth grade class, I stopped class at one point to introduce the three rhetorical appeals: ethos, pathos, and logos.

One student excitedly said, “you can use those almost everywhere.” And another one said, “I see those everywhere.”

In the simplest sense of the term, that’s education. One person opens a door for another. Or a window. Or walks them just slightly around a corner and points: look at that!

Assuming both of the above students convert their new knowledge into some kind of practice or action — even a slight one — they will have more control over their world, more agency. They might be a little more bold in what they dream and how they make their dreams a reality.

I’ll assess them on the terms, and some possible extensions and applications, because I think the concepts matter. They will use the assessment to both show me what they know and to solidify what they have learned.

Slowly, simply, the simpler the better, and layer by layer by layer: teaching and learning. School. Freedom.

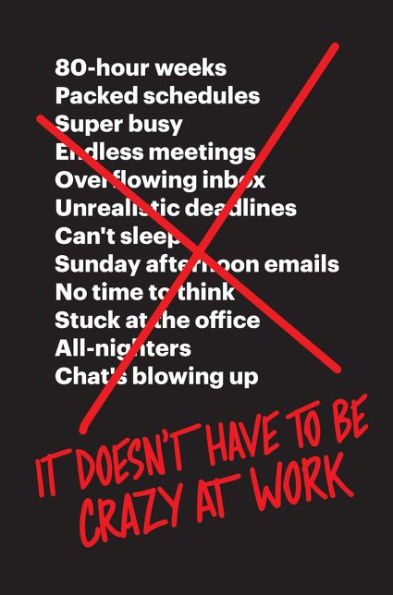

I’ve long been a fan of David Heinemeier Hansson, co-founder and CTO of Basecamp. Though I don’t use his product, I do read his books because they tend to argue for a sane, slow, and steady approach to work and productivity. His latest book, in that sense, is utterly “on brand.” It’s called It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work.

Today I’m going to highlight an excerpt from one of Hansson’s recent interviews (published by a company called Owl Labs) because it cuts against an approach to calendaring that I’ve been advocating over the past few years. I encourage people to be efficient — and respectful of one another’s time — by using “youcanbookme” type applications, polling software, or transparent calendars to schedule meetings. I’ve argued that such practices eliminate frustration for the people being invited to meetings. Hansson, on the contrary, prefers to leave the frustration in the process. In particular, he wants the people calling meetings to have to work to build those meetings into people’s schedules. In his words:

One of our strategies for protecting people’s time is by skipping the game of calendar Tetris at Basecamp. At most companies, calendars are shared and open, so every employee sees each others’ schedules and set meetings during their colleagues’ open blocks of time. When everyone’s time is available in that way, it’s hard for people to plan their days around doing their best work, and instead, they get pulled into meetings. We want coordination and taking other people’s time to be manual, annoying, and difficult.

Here’s how we do it: If you’re trying to coordinate a meeting between four people, there’s no technology to help you do it. You have to contact each person individually and ask if they can meet during your proposed time. And if someone says no, you have to keep going back and forth with everyone to find a time that works. In short, it’s a pain in the ass. Because you can’t see everyone else’s calendar, you’re forced to do this manual song and dance to set a meeting, and that’s exactly how we like it, because people won’t go through that inconvenience unless they really need to hold a meeting. The policy also helps communicate that that open space on someone’s calendar doesn’t make them available for wasting time. The default policy is that open space on someone’s calendar means they’re working, which in most cases, is a better use of time than a meeting.

https://www.owllabs.com/remote-work-interviews/david-heinemeier-hansson

Take the frustration out or leave it in? Most of us would quickly say, “take it out!” In the eyes of a workplace designer (i.e., boss) with as keen an eye as Hansson’s, frustration itself becomes another tool to serve company mission. I’m going to chew on that thought for a while.

Today, we had an in-service day after a two-week break. We started an hour later than usual and ended an hour early. In between, teachers mainly talked shop. They talked about approaches to what they teach and how they teach. They talked about observations they had made of other teachers, often in other disciplines. They talked about what they learned from videotaping their teaching or being observed or evaluated. It was an outstanding way to re-start school.

In part, I think it worked because it wasn’t over-programmed. We “designed” for slow conversations, gentle collisions, catching-up, being together. Tomorrow, when the students show up, I expect the school to feel warmed up and a bit warmer. Ready to convince 425+ young people to begin learning — in high school — again.

This past week I wrote posts about:

Now they’re all in one place for you, easily accessible as you sip your morning coffee and make your weekend plans.